Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest: An Enduring Legacy part 2

This bridge stretches across the Santeetlah Creek inside the Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest.

By Dr. Thomas Cloer, Jr.

Special to The Courier

Nat Cloer Explains

His Grandfather’s Fears

My brother, Nat Cloer, and Carl T. Cloer Sr., my dad, while working for Gennett Lumber Company here in Pickens, wisely decided to form their own company. Thus, Compton and Cloer Lumber Company was formed. Then, in 1981, Nat formed his company, West Union Hardwoods, in West Union, where he very successfully produced some of the finest lumber ever

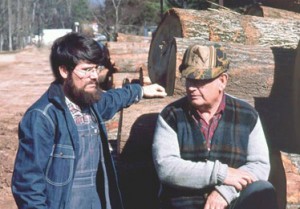

Courtesy photo

Author and Carl T. Cloer Sr. are pictured in Pickens with logs from the Jocassee Gorges lake bed.

to be manufactured in South Carolina or the nation.

For decades, Nat produced millions of board feet of lumber, and after sterling success was recognized as one of the shrewdest and most sagacious lumbermen ever in the business. Nat Cloer, named after Nat Gennett, explained some of the problems W.T Cloer, our grandpa, knew he would encounter at the sawmill with the trees now in Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest, the largest stand of virgin deciduous trees left in America.

“Tom, one of the first problems was just trying to keep the giants on the log carriage,” Nat explained to me. “The carriage dogs (universal sawmill language for the sharp steel barbs that hold the log on the carriage) couldn’t grab hold that size of a giant log. When I cut a really big log that the  dogs couldn’t grab, we would of necessity hammer giant wooden wedges directly under each log on the carriage knees so the log couldn’t fall forward off the carriage and kill somebody.

dogs couldn’t grab, we would of necessity hammer giant wooden wedges directly under each log on the carriage knees so the log couldn’t fall forward off the carriage and kill somebody.

“When we were in Pickens and they brought the biggest trees from where Jocassee and Keowee lakes were formed, we had a slow, careful process to deal with each forest giant. We had to first cut trenches in the logs in several places using long-blade chain saws, then fill the trenches with coarse black gunpowder and blow them into halves that we could finally accommodate on the carriage. That was a slow process, and it worked better with some species than with others.”

Nat continued.

“Tom, keep in mind the fact that you have the same number of men working at the same wages whether your logs are 24 inches or 60 inches in diameter as in Joyce Kilmer Forest,” he explained. “If I could order my logs, I prefer logs about 24 inches in diameter and 12 feet long. A 24-inch log, 12 feet long, would allow the crews to cut one inch or thick boards easier and faster than a log five feet in diameter and 16 feet long that the carriage dogs couldn’t hold. I could cut any thickness I wanted. I also didn’t have the grand problem of big wide boards from huge logs warping, cupping and having thin ends on lumber when I used the smaller and shorter logs.

“Grandpa Cloer recommended what he did about the trees in Kilmer Forest because he knew the bottom line was costs versus revenues. He knew the crews could produce more board feet of lumber, with fewer problems, using logs that were easier to get to the mill and that were more manageable once they arrived,” Nat said with a final nod of approval.

How the Joyce Kilmer

Memorial Forest Had Survived

How had this massive, unequalled stand of deciduous trees escaped? First, the Little Santeetlah Creek and this living museum were not bothered because of its isolation in a far southwest corner of mountainous North Carolina. That area was the domain of the Cherokee until after their removal to Oklahoma. This area was then settled less by Europeans than all the rest of Appalachia. White Europeans were not present in the area until 1840. Because of its location and remoteness, it was virtually one of the last mountainous regions to be logged.

Around the turn of the 20th century, Belton Lumber Company bought what is now the Kilmer Forest and made elaborate splash dams for moving the massive trees, and went bankrupt doing it. In 1915, Babcock Lumber Company began to log on the opposite watershed and north of Poplar Cove on Slickrock Creek. In the early 1920s, the construction of the Calderwood Dam on the Little Tennessee River in that watershed blocked Babcock’s access to Poplar Cove from that direction, from the north.

That’s one reason Slickrock Wilderness Area was added to Joyce Kilmer property in 1975. There was fabulous old-growth timber there that Babcock had to leave as they went up the watershed that is just across Stratton Bald from Poplar Cove and the Little Santeetlah (I personally have walked it all). Then, the damming and construction of Santeetlah Lake covered the railroad access from the only other possible direction, from the east. The lack of a rail system to transport the massive logs was a most critical factor for the survival of this American wonder.

In 1926, Gennett Lumber Company bought more than 20,000 acres on Santeetlah Creek, Deep Creek and Bear Creek in Graham County, N.C., which included the property that is now Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest. However, as the Great Depression tightened its grip on the American economy, Gennett Lumber Company began to falter, and my Grandpa Cloer became worried.

Fortunately, for those of us interested in knowing what transpired, Andrew Gennett left us details, blow by blow, in his memoir. According to Gennett’s memoir, “Sound Wormy,” at the end of 1929, Gennett Lumber Company was in debt $541,000. In 1930, lumber sales fell from 15 million board feet a year to six million. In 1931, and up to the time of Gennett’s sale of the land to the U.S. Forest Service, Gennett Lumber Company was able to sell only two million board feet of lumber per year. Gennett was going even more deeply into debt as the company had bought land where the timber had to be cut and the costs were much more than the sales. Seventeen million feet of their lumber lay in lumber stacks unsold.

In 1935, after W.T. Cloer’s recommendation, Nat Gennett sold 13,500 acres on Little and Big Santeetlah Creeks to the U.S. Forest Service for $28 per acre. Land was selling for $4 an acre at this time during the Great Depression. The U.S. Forest Service really wanted this land and was willing to meet Nat Gennett’s offer. (Andrew Gennett had suffered a stroke at Wolf Mountain, where my grandpa was superintendent; Nat Gennett had to finalize the deal.) Of this total purchase, 3,840 acres became the Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest when dedicated by the United States in July 1936.

Andrew Gennett said in his memoir, “I saw no way by which we could get the amount of money necessary to erect and operate that mill. … It was with great joy that I cashed this check … and paid off the loan they had carried for us for nearly 10 years. I also paid off various debts to insurance companies and other debts that the firm had acquired. Nat and I felt that we were again even with the world.”

Writers have suggested that the Gennetts could have built a rail system, and that Gennett Lumber Company could have completed the logging and milling of the forest giants. However, Grandpa Cloer knew that these were the darkest times of American economic history. Inordinate expenses by a company could lead to certain bankruptcy in the mid-1930s. Grandpa Cloer knew this, and thus was most skeptical about the costs versus revenues with this Little Santeetlah stand of gigantic timber.

Gennett Lumber Company rebounded after the terrible depression. The company had successful mills that were parallel with my life in the 20th century at the following locations: Clay County, N.C., Ellijay, Ga., Stinking Creek, Tenn., and Pickens.

Was Grandpa a magnanimous philanthropist? He had 11 children and two orphans at the table with Grandma and himself during the worst economic times in our history as a nation. He was brilliant at keeping down costs while maintaining steady screams of saws that were producing lumber at sawmills. Grandpa would love the fact that 50,000 people each year visit Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest, and that his recommendation helped save the lush forest. But, indeed, the motivations of most sawmillers involved in this era were most likely not philanthropic. They were all, Grandpa included, just trying to survive.

Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest

Before you plan your next vacation, I recommend this sacred place if you haven’t visited yet. Not only is Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest the largest, most spectacular stand of virgin deciduous trees left in the United States, but you get to see how our southern Appalachian Mountains appeared before any Europeans arrived. This memorial forest is located in the Nantahala Mountains of Graham County, N.C., near Robbinsville. The forest is the most impressive I have ever seen anywhere. I have been around sawmills since the 1940s and have seen many forest giants here, in South America and Europe. I have seen some of the best hardwoods in the Appalachian Mountains before and after their removal from the watersheds. But none compare, in my experience, with the diverse giants in this wilderness. Just south of The Great Smoky Mountains National Park, 3,840 acres of Kilmer Forest thrive on both sides of the Little Santeetlah Creek that flows into the Big Santeetlah, Cheoah River, Little Tennessee River and the mighty Mississippi.

The Little Santeetlah Creek drains a watershed that my Grandpa W.T. Cloer knew as Poplar Cove. None of the trees in this lush paradise ever encountered a “misery whip,” a term used by loggers when they referred to a crosscut saw requiring two men to pull it. None of the trees in Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest have ever been harvested. Some of the trees are more than 400 years old. This forest amazingly has more species of trees than all of Europe! Oh, the diversity which is there to behold, unique to the Appalachian Mountains! Behold the yellow poplar, red and white oak, American beech and sycamore! See the basswood, the red maples, Frasier magnolias, yellow birch, the Carolina silverbells and the bulging buckeyes!

The Joyce Kilmer Memorial Trail, a two-mile loop trail, will take you through this incredible outdoor museum that has hardly changed since the time of Columbus. The trail is a walker’s paradise, a hiker’s heaven. The old giants that have died become nursery logs that allow another generation of trees to gain a foothold. When I was there last with my grandson, Harvest Wolf, I pointed to a poplar stump about 7 feet in diameter with a healthy hemlock tree growing out of the stump.

There are those rare times when one sees a natural wonder that holds such grandeur and majesty as to defy description. One feels emotions that are too strong to capture in mere rhetoric. In such instances, it is best, I think, to simply say, “See for yourself.” The Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest is just such a natural wonder. I think you will feel, as I felt, the need to take off shoes when you realize you are indeed on holy ground.

The author is Professor Emeritus, Furman University, and was the first faculty member in Furman’s history to earn both Meritorious Teaching and Meritorious Advising Awards. He was the first South Carolina Professor of the Year, chosen by the late Governor Carroll Campbell and the South Carolina Commission on Higher Education.