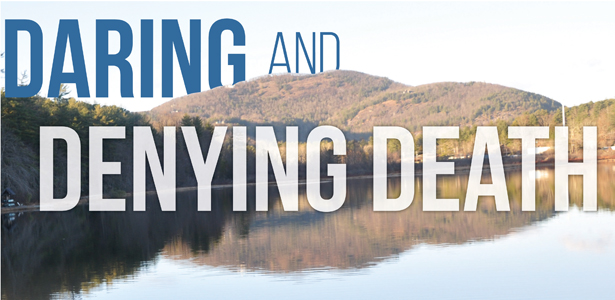

A mountain girl escapes with her life at Cashiers Lake

The year was 1939.

The place was Cashiers Valley, N.C. Several members of the Cloer family living in Cashiers were working at the sawmill that my Grandpa, W.T. Cloer, was operating at Wolf Mountain, near the head of the Jocassee Gorges.

It was summer, and it was hot!

This was unusual for Cashiers, since the average July high temperature there is 78 degrees, and at an elevation of 3,485 feet, “hot” was not really normal.

I love Cashiers, because the first memories of my life are there as my older brother, Nat, and I dug newt lizards out of the bank near our house on the Eastern Continental Divide, and ate chinquapins (dwarf chestnuts) from a productive tree at the front of our mountain home. In Cashiers, Highway 107, coming from South Carolina, junctions with Highway 64, which crosses the North Carolina mountains. Cashiers is really quaint; there are no honky tonks or fast-food chains.

Cashiers Lake is probably one of the most pristine lakes in the world. It collects tributaries forming at the highest elevations in Jackson County on the Atlantic side of the continental divide. The water is the origin of the mighty and majestic Chattooga River. No place is more refreshing on the hottest days of the year than the cold waters of Cashiers Lake.

There are five places in Cashiers on the National Register of Historic Places, and my parents worked at two of them. Mom and my Grandmother, Bonnie Moody, worked at historic Fairfield Inn, and my dad, Carl Cloer, worked at High Hampton Inn as a golf caddy in the 1920s. The guys in Pickens were always amazed at the accurate golf touch of Dad, somewhat out of character for a renowned mountain man. Dad actually started playing golf with other caddies of Cashiers at a very young age, and was a proficient golfer well into his 70s.

Courtesy Photo

Effie Cloer McDevitt with Betty Lou, Barbara and Thomas Edward McDevitt.

My mom, Grace Moody Cloer, was 15 years old at the time of this story, and swam regularly in Cashiers Lake with the Cloers. Her future husband, my dad, was a central figure in the scene unfolding on this hot summer day. He was 22 years old, and he and Mom were friends at this point in their lives. Mom was swimming this day with her sisters, Lucy and Maxine Moody, ages 14 and 13, respectively. They were allowed to swim if Effie Cloer McDevitt, Dad’s oldest sister, was along.Aunt Effie was the oldest of the eleven children of W.T. and Pearl Cloer, my grandparents, and Effie was totally dependable. She was married, had three children, widowed and had just turned 30 years of age. Mom’s mother was very fond of Effie, and Grandma Bonnie said her children could swim if Aunt Effie took them to Cashiers Lake in her truck.

Mom remembers the day in high school in 1938 when someone came to take two Cloer girls, Tate and Lib, from Glenville High School near Cashiers, because Effie’s young husband, Thomas McDevitt, 31, had died during the night. On the sultry summer day of this story, Aunt Effie had her three young children, fatherless at such an early age, enjoying the water of Cashiers Lake.

On this day, Mom remembers that A.J. Cloer, 13, Gin Cloer, 14, Tate Cloer, 16, Zona Cloer, 24, and Effie Cloer McDevitt, 30, were all enjoying the refreshing ice water of Cashiers Lake high in the Blue Ridge Mountains. Effie also lived directly atop the Eastern Continental Divide in Cashiers.

All of Dad’s brothers and sisters were athletic. Dad was a phenomenal swimmer and diver, and was very fast on his feet. Dad’s other brothers, Andy, Bob and A.J., were also athletes. I can remember the first time as a young lad seeing Dad dive and swim with his sister, Lib, as Lib’s husband, Vernon Pruett, backed his huge lumber-hauling truck to the steep banks of Holly Creek in the high mountains of North Georgia. We all were amazed at the athleticism of Dad and his sister as they performed dives from a diving board hastily constructed on the back of the huge truck.

Serendipity: Dad Tags Along

W.T. Cloer, my grandpa, had actually told the younger Cloers that he didn’t want them to go swimming this day. Mom said that she knew that A.J., Gin, and Tate had been asked not to go. W.T. remembered that Cashiers Lake was where a killing had taken place when Kay Baumgarner had killed Frank Bryson there on the dam. Furthermore, beautiful teenage girls in pretty bathing suits could — and did — bring out the gargoyles.

Courtesy Photo

From left, Carl Cloer, Tom McDevitt, Zona and Andy Cloer are pictured on the truck mentioned in the story.

Aunt Effie took her truck to Cashiers Lake this day and took her three small children with her. Life was hard as a widow at age 30. Any change of pace was welcomed. The other Cloer children clamored to find a seat and get set before Aunt Effie started double-clutching the old truck. Double-clutching expedited the changing of gears in old straight-shift truck transmissions without grinding of the gears. It involved depressing and releasing the clutch to shift the gear to neutral, then depressing and releasing the clutch in the next gear.

Dad was trying to recuperate after a hard week in the sawmill at Wolf Mountain, and said he was going to rest this one out.

“Oh! Come on, Carl! Go with us!”Aunt Tate called.

“It’s more fun when you go, Carl,” Aunt Gin urged.

“You all can shiver in that ice water without me,” Dad answered.

“Get on, Carl, I’ll need help with this mob,” called Aunt Effie.

Courtesy Photo

Effie and W.T. Cloer.

When Dad started to back away from the old truck, Aunt Effie gassed it and started rolling. Dad told me how he ran and jumped on at the very last second without Aunt Effie slowing the old truck. Serendipity explains it to some; others would call it fate.

Cashiers Lake is not a pond; it covers several acres, and is deceiving as to distances across it. Zona, my dad’s sister, two years older than he, called to the others, “I’m going to swim across the lake and back! Who wants to go?”

“Not a good idea, Zona,” Effie called. “That may be too far!”

But, Zona was already swimming with an overhanded crawl stroke toward the far shore.

Dad didn’t have his swimming trunks. Who knows? He may have been going to scope out Mom in her bright red bathing suit. Mom and her siblings had moved to Sapphire, near Cashiers, when their young father, Weaver Moody, had died on Christmas Day, also just in his thirties. My Grandmother Moody had moved to Lupton’s Lake at Sapphire, N.C., as caretakers of the property. There, Mom and her siblings became excellent swimmers and lovers of ice water. I can remember being amazed as a small child at how well Mom could swim. She, her siblings, and the Cloers were all like a flock of goldfinches in a birdbath on this hottest day of the year. They slapped the water and splashed each other as they squealed in delight.

Daring Death

“Wait! Wait! Stop splashing! Something’s wrong! Oh God! Oh God! Somebody help Zona! Something’s wrong!”

Dad heard the screaming and quickly ran to the water’s edge to see what the commotion was.

“Somebody help Zona; she’s drowning in the middle!” someone screamed.

Dad jerked off his shoes and shirt and hit the water thrashing toward his sister. Dad told me several times about each thing that happened. I remember vividly that he said Aunt Zona had gone down several times, and was in serious trouble when he reached her.

“Now, Zona, honey, don’t wrap your arms around me, or we’ll both drown!” Dad called as he approached her.

“Just let me get hold of you!” Dad urged.

“Hurry, Carl! I can’t stay up!” Zona choked and screamed.

By the time Dad reached Aunt Zona, she had panicked and had taken on a large amount of water. Dad said when he was in reach, she immediately wrapped her arms and legs around Dad in an attempt to stay afloat. But, instead, she and Dad sank as Dad fought feverishly to break his sister’s grip. He surfaced long enough to get a large gasp of air before sinking in Aunt Zona’s grip for the second time. Dad said that Aunt Zona finally loosened her grip on him, and on her life as well. Dad thought she was gone as he grabbed her hair and pulled her toward the shore, and cried out for the others to come and help. Aunt Zona was completely lifeless, had sunk underneath, and Dad was now pulling her by her beautiful hair.

The others ran and swam toward Dad and Aunt Zona. They lifted and dragged at her motionless body. People were crying and screaming.

“Is she dead? Oh my God! Don’t let her die! Come and help! Please! Come and help!”

Death Denied

In her 90s now, Mom remembers well what happened next. Several in the throng of sawmill folks grabbed Zona’s lifeless and beautiful young body and turned her on her stomach. They began to push down hard on her back and sides. Mom said that when Aunt Zona was turned over, water flowed out of her lifeless mouth. When they began pushing hard, water gushed out. They continued until Zona started coughing wildly, and then, denying death, started breathing. The mountain girl cheated death that day. She and my dad also formed a tight bond between brother and sister that lasted for the rest of their lives.

I can remember visiting Aunt Zona when she became a successful entrepreneur and operated an appliance store. She had problems breathing every time I saw her, and was always using this weird apparatus to get oxygen into her lungs. She would wheeze when she talked, and would suffer lung problems for the rest of her life. Dad attributed this to the drowning. Who knows? Mom claimed Zona had always suffered with asthma. Dad argued, somewhat sarcastically, that the near-drowning probably didn’t help Zona.

What I remember about Aunt Zona was how kind and gentle she was every time I saw her, and how very much she loved my dad. She always called me “Sweet Tommy,” and she and Dad called each other “Honey.”

“Honey, I remember that you pulled me from the grave. Sweet Tommy, your dad saved me from drowning; I am alive because of him.”

Conclusion

I think I know now what happened that day. I never heard anyone say it, but I believe I know what happened. A later experience of mine will help explain.

My wife and I were living in graduate housing at the University of South Carolina in Columbia in 1972. I was completing requirements for a Ph.D. degree. My son, Carl Thomas Cloer III, Tom-Tom, was in kindergarten, and was the life of each party at every gathering of kids from graduate housing. One of the mothers was responsible for choosing a child to carry a scepter for the 1972 Football Homecoming Queen for USC. The lady asked us if Tom could possibly carry the Homecoming Queen’s scepter on a pillow to midfield at halftime.

Tom was thrilled and immediately said, “Yes! Yes! Can I, Mom? Can I?”

Of course, Elaine and I were thrilled to have him chosen.

“Oh! That would be great, Tom! Of course you can!”

Tom was a bundle of energy, and was ever in motion. Then, on the morning of the queen’s coronation, life happened. Tom was noticeably discontent and listless. By lunch, we knew something was wrong. Tom was gasping for air, and his medicine for diagnosed bronchitis wasn’t helping. By afternoon, Tom was really struggling to breathe.

“Tom, I’m going to call the lady in charge of the queen’s court, and tell her you are very sick.”

“No! Dad, No! They are depending on me!” he begged. “Please, Dad! Please don’t! I can do it! I promise! I can do it!”

I looked at his mother. “Your call,” she said, almost in tears.

I carried Tom in my arms to the stadium fence. I will never forget how his little shoulders raised as he tried to fill his lungs with enough oxygen to walk. But walk he did, with shoulders raised to his ears. He performed admirably, and upon reaching the sideline in return, he collapsed into my arms and we hurried home.

That was the first attack of his chronic asthma; it continues to this day. I learned a great deal, and know more about asthma now, and the effect it can have on an athletic body. I had a big fullback in the backfield with me in football. When his asthma flared, all bets were off.

Aunt Zona, who later suffered with asthma all her life, unfortunately had a serious attack in the middle of Cashiers Lake that day in 1939, and if not for Dad, she would have dared death that hot, sultry summer day and lost.

Tom Cloer is a professor emeritus at Furman University. He has published widely, including several books, computer software, journal articles and numerous stories of Southern Appalachia. He was the first South Carolina Governor’s Professor of the Year.