An in-depth look at of one of the world’s great wonders

By Dr. Thomas Cloer, Jr.

Special to The Courier

I have always been interested in caves. I have tried to psychoanalyze myself to understand why.

I think Mark Twain had an early effect on me. I do remember vividly the writings of Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens) about Tom Sawyer and Becky Thatcher. Becky was Tom Sawyer’s sweetheart. They were on a ferry boat ride that stopped to visit McDougal’s Cave in the novel, “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer.”

(Samuel Clemens) about Tom Sawyer and Becky Thatcher. Becky was Tom Sawyer’s sweetheart. They were on a ferry boat ride that stopped to visit McDougal’s Cave in the novel, “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer.”

McDougal’s Cave was very dark and had many different branches and passage ways. Becky and Tom wandered off and became separated from the group. Since Becky was to spend the night with a friend, the two weren’t missed for a long time.

They encountered waterfalls, bats and a cool spring. Tom had Becky stay by the spring while he tried to find a passage out of the cave. I remember that Becky told Tom she was going to die, and wanted Tom to be holding her when she passed. They later fell asleep, awoke and shared a piece of cake that Tom had saved, and realized they were really lost.

So, Tom and Becky were lost in a dark cave, which also, by the way, housed a violent man. They eventually discovered a small, well-concealed opening to the outside world. Tom Sawyer later took Huck Finn and showed him how hidden it was.

There was great rejoicing after Tom and Becky were found. They had been missing for three days. Judge Thatcher, Becky’s father, immediately locked down McDougal’s Cave. The judge had it fixed so no one else could ever enter. Wait! Injun Joe was in there!

It was in the 1950s when I first encountered “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer” and “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.” Both novels were emotional for me and really left a lasting impression in my mind.

Then, in the 1960s, I was in East Tennessee, where I got to follow my attraction to caves. Norris Lake was a Tennessee Valley Authority lake that was near where we lived. East Tennessee is replete with enormous rock outcroppings.

I explored the lake thoroughly and discovered a secluded, huge cavernous outcropping where I could pull my small fishing boat into a cave and camp. I would go there in a storm and be perfectly dry.

No one else had found it because the roof of the cave was so low at the entrance, and my little wooden boat was small enough to enter. Once inside, the roof was a comfortable height. I would run trot lines for catfish and freshwater drum all night. I can remember violent storms while my boat  and I were in the cave, totally safe and in the dry.

and I were in the cave, totally safe and in the dry.

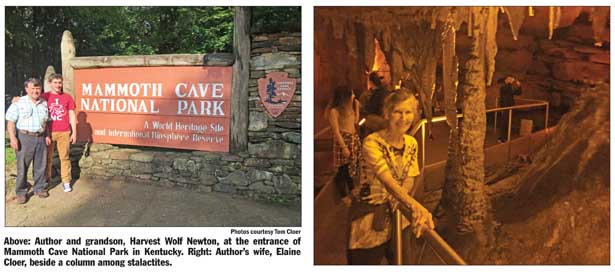

My wife, Elaine Kowalski, and I met in college in Williamsburg, Ky. We married while there and later graduated from Cumberland College, now the University of the Cumberlands. We started teaching in the one-room schoolhouses of Appalachia in the Kentucky mountains.

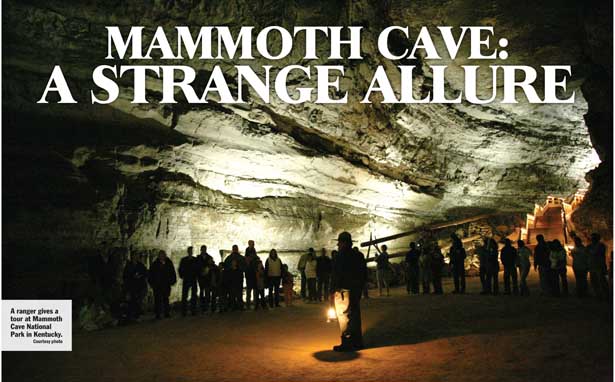

The longest cave in the world is Mammoth Cave in Kentucky. I have walked for miles and spent many hours in Mammoth Cave. I’ve walked the cave day and night. At night, the lights are turned off and one walks by lantern light.

Mammoth Cave

Mammoth Cave in Kentucky is by far the longest cave in the world. A young United States of America didn’t have the fancy edifices that served as tourist attractions in the 1800s as Europe showcased. We did have, however, our wild and natural wonders such as Mammoth Cave, the Grand Canyon and the giant sequoias.

Mammoth Cave was formed over millions of years when water, working its way downward, dissolved the limestone and formed huge and small passageways, stalactites, stalagmites and columns. Mammoth Cave was first visited about 4,000 years ago by Native Americans. Then, in was rediscovered by Europeans around 1798. Mammoth Cave, with its miles and miles of branches, really helped our national identity by being truly one of the world’s greatest natural wonders.

Now, of course, it’s a great national park. The park on the surface consists of 52,830 acres in three different counties of Kentucky. However, no one really knows how many miles exist of Mammoth Cave with its many branches. Four hundred miles of Mammoth Cave have been surveyed as I write. More is surveyed and added every year. It is currently more than twice the size of the second-longest cave in the world. That cave is in Mexico.

An Early Benefit in

War with England

Mammoth Cave really began to be widely known early in the 1800s. It provided saltpeter for black powder guns during the War of 1812 with Great Britain. The War of 1812 is usually referred to as the Second War of Independence. British troops invaded America, captured Washington, D.C.. and burned the White House. The British were attacking Fort McHenry in this war when Francis Scott Key penned what would become our national anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

As I explored Mammoth Cave, I could see all the mining pits, the hollow hardwoods used by slave workers as huge pipes, and the old structures used to get the saltpeter to the surface more than 200 years ago. Centuries in the creation of a cave such as Mammoth Cave, however, represent a relatively short period.

Mammoth Cave was a tourist attraction long before it was a national park. A slave, Stephen Bishop, “property” of the saltpeter mine owner, was the first individual to explore many miles of the cave. He was the first to cross the “bottomless pit,” and the first to discover an evolutionary wonder, the solid white fish with no eyes. There are also solid white crayfish with no eyes.

Bishop became a well-known, self-educated teenage tour guide in the early 1800s. By 1816, people started really visiting the cave. Two other slaves of the mine owners, Mat and Nick Bransford, became legendary guides. The Bransford descendants served as tour guides for more than a century.

National Park, World Heritage Site and

Biosphere Reserve

Mammoth Cave was fully established as a national park in 1941. Forty miles had been mapped. Of course, the process of surveying and mapping has improved greatly. We now know that the cave system underneath the earth goes far beyond the surface boundaries of the park. Because Mammoth Cave is a great wonder of the whole world, it was named a World Heritage Site in 1981.

This whole cave system is now a very special place to study approaches for managing peoples’ interactions with such natural wonders and the impact people have. Because of this, Mammoth Cave has been named an International Biosphere Reserve, truly an international treasure. This is why cave visitors and their behaviors are so carefully guided and controlled.

As I walked for miles in the cave, I was awestruck by the mammoth-sized passages that serve as totally natural and undeveloped subway systems with none of the metal, noise and mayhem. In fact, I would challenge anyone to find a quieter, more solitary place on our planet Earth. One can readily see why it is an international treasure.

The Frozen Niagara in the cave is one of the most unique visual presentations I have seen. One can’t help but wonder as one wanders inside the cave. The creation of the stalactites hanging down and stalagmites reaching up and touching have left “columns” that are most picturesque.

Variety Within the Cave

Another striking aspect of Mammoth Cave is the difference in the cave’s landscape. There are sharp differences in altitude and changes from rooms to rotundas, from passages to church and hospital sites — what?

The cave has a depth of 379 feet. That is as far under the ground as the entire field length of a football stadium.

Before the cave became a national park, the Methodists actually held church in a room of the cave. The preacher would gather all lanterns where he stood and presented the sermon. He had a captive audience for as long as he wanted to preach.

A tuberculosis hospital was also housed in the cave at one time. I was really interested in this, because my great-grandmother died of tuberculosis.

Grand Avenue in the cave leads to 670 stairs. There are really narrow canyons, some unbelievable rooms and rolling hills after rolling hills. I walked for four miles and several hours in this area. It is “physically demanding,” as advertised by the park. Does it compare to the Jocassee Gorges? That is comparing apples and oranges. The cave is dark, stark, different and cool.

When one approaches the historic entrance, the cool air billows out of the cave in summer like a mammoth air conditioner. The cave underneath the surface of the earth is different from a vibrant, flourishing landscape above where sunlight provides all the light everything needs to flourish, grow and reproduce.

There are about 130 forms of life in the cave, most of these very small, like the cave cricket. The bats aren’t even there in summer. They live outside in the park’s old hardwood trees. A tiny owl welcomed me in one of the rooms. On the earth’s surface, scientists talk about animal species alone being in the millions. There is no comparison with the outside world, thus making this dark, stark place so different and apparently attractive to people worldwide.

Before Mammoth Cave became a national park, there were early land owners who had cave entrances on their properties. There are now several of these entrances in use in the national park. This was a primary means of the land owners making a living by guiding tourists through these caves. Competition became a natural outgrowth of guiding tourists who, like myself, are attracted by dark, silent caves.

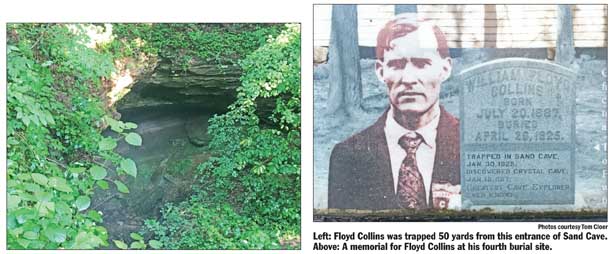

Floyd Collins was an early land owner driven by this competition to find newer entrances to the vast cave system. On his property was Sand Cave. As I walked to Sand Cave in the park, I was reliving everything in my mind that I could remember about Collins. In Kentucky, Collins is known as a legendary cave explorer.

Floyd Collins:

‘the Greatest Cave

Explorer Ever Known’

Collins entered Sand Cave on his property Jan. 30, 1925. He was trying to find another entrance to Mammoth Cave. It is now known that Mammoth Cave was actually underneath where he was exploring. Collins always left his jacket outside the entrance to alert everyone that he was inside the cave.

I will never forget “Fat Man’s Misery” and “Tall Man’s Misery” in Mammoth Cave. These are located near the historic entrance of the cave system. One begins by traveling down wide, expansive portions of the cave. Then come the squeezes. I mention these squeezes (my naming) because it was in this type of cave aisle that Collins was trapped.

A relatively light collapse of rock pinned his leg in a place where the leg was totally inaccessible from Collins’ front, or the entrance of the cave. There are very few inches to maneuver in some of the squeezes with very narrow walls and/or low ceilings.

Media Circus

Friends discovered Collins’ jacket outside the cave, and soon located him where he was trapped. They brought him a light and some food. They did this daily while one of the biggest media events of the early 20th century took place outside the cave’s entrance. A circus-type atmosphere occurred when hundreds of cars brought people who had heard Collins was trapped.

How did so many hear about this? William Miller, a journalist who was also a rather small fellow, got in close to Collins in the cave. He actually interviewed the trapped explorer and won a Pulitzer Prize for his publications in the Louisville Courier-Journal. His reports by telegraph were published by many different newspapers across the United States and abroad. His reports were also sent to homes and other strategic places by a new medium, broadcast radio.

I have actually lodged in Cave City, where the nearest telegraph station was located at the time. Cave City, however, is miles from the entrance of Sand Cave from which telegraphs were sent. Two amateur radio operators at Sand Cave provided the critical link for the information to reach the press and the authorities so quickly.

This, however, is what brought the huge crowds by the thousands. Vendors set up shop and started selling food and souvenirs. Picnic outings were crowded into every available nook and cranny. Carload after carload pressed toward the entrance of Sand Cave. After four days, the first 50 yards of passage to Collins collapsed in two major places. Only voice contact was then possible. The rescuers, undeterred, gave up on the main cave passage, and started a 55-foot shaft that, with a lateral shaft, was completed on Feb. 17. They broke through after 18 trying days to the trapped cave explorer. They found Collins dead from exposure.

Conclusion

The shaft that broke through to Collins was actually above and in front of Collins, and still would not allow the pinned leg to be removed. Since Collins died doing what he loved, and where he loved to do it, it was decided to leave his body where it was pinned, and fill the cave with debris. A service was held on the surface, and Collins was now officially buried — for the first time.

However, Floyd’s brother, Homer Collins, was not satisfied with leaving Floyd’s remains in the cave. He, with the help of friends, dug another tunnel that broke through where they could finally dislodge Floyd’s pinned leg. They removed his remains on April 23, 1925. Collins was then buried for the second time on the Collins family farm near Crystal Cave.

However, that farm with Crystal Cave was subsequently bought by a different family. The new landowner disinterred the remains of Collins, and displayed them for several years in a glass-topped coffin in his privately owned Crystal Cave. In March 1929, Collins’ remains were stolen from the cave, but were strangely found in a nearby field. (I suspect that the body had dropped during the theft from whatever held it.) The body was then placed in a chained casket and buried (for the third time) in a secluded portion of Crystal Cave, now called “Floyd Collins Crystal Cave.”

When the National Park Service bought Crystal Cave, they relocated the grave of Floyd Collins for his fourth burial to Mammoth Cave Baptist Church cemetery. This is where I gave Floyd my highest respect, even though he may not have lived up to his billing in one of the press releases as “the greatest cave explorer ever known.”

About the author: Thomas Cloer, Jr. is a professor emeritus, Furman University. He was chosen South Carolina Governor’s Professor of the Year in 1988 by the late Gov. Carroll Campbell and the South Carolina Commission on Higher Education. In Kentucky, he received Cumberland College’s Outstanding Alumni Award and was placed in Cumberland College’s Hall of Honor. He served as a consultant for several county school districts of Kentucky, and was nominated for the University of Kentucky Libraries Medallion for Intellectual Excellence.